How the Next President Can Help the Middle East

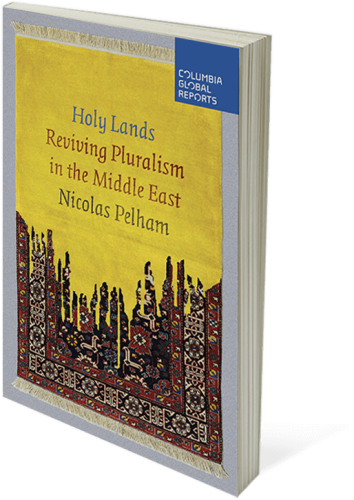

"It’s hardly surprising, given the mayhem and misery across the Middle East, that people who know and care about the region are scratching their heads trying to explain, never mind solve, its overarching problems," Ian Black, The Guardian's Middle East editor, wrote in his recent review of Holy Lands: Reviving Pluralism in the Middle East.

There are those who believe that the solution to the Middle East lies in liberal democracy—it represents the governance we know best, and what works for the West ought to work for the rest, as the administration of George W. Bush disastrously demonstrated after the Iraq War.

But, as Patrick Oathout at New America recently noted, there are "those who believe democracy must be built on the back of contemporary Islam, and that failed state-building in Iraq, Afghanistan, post-Arab Spring, and even post-Sykes-Picot are empirical evidence for their side."

This is the starting point of Economist correspondent Nicolas Pelham's Holy Lands, as it begins by laying out how the fall of the Ottoman Empire gave rise to secular-inspired and Western-backed governments that turned religion into a nationalistic cause. "Pelham, like many scholars, believes present sectarian violence in the Middle East is the result of this religious nationalism," Oathout writes, "which in turn has displaced ethnic and religious minorities, further eroding the region’s diversity."

This is the starting point of Economist correspondent Nicolas Pelham's Holy Lands, as it begins by laying out how the fall of the Ottoman Empire gave rise to secular-inspired and Western-backed governments that turned religion into a nationalistic cause. "Pelham, like many scholars, believes present sectarian violence in the Middle East is the result of this religious nationalism," Oathout writes, "which in turn has displaced ethnic and religious minorities, further eroding the region’s diversity."

The result is decades of religious conflicts and sectarian strife, culminating in today's Sunni-Shia clash and the rise of the ISIS "caliphate." By advocating for less religion, the West ended up prompting a backlash that gave rise to fundamentalism in the Middle East. "Sects matter more than ever," as Black points out, because governments uninterested in proper nation-building use it as "a vehicle for the competition of rival states"—sectarianism is no longer the natural state of a pluralistic region where different religions and sects live side by side with one another.

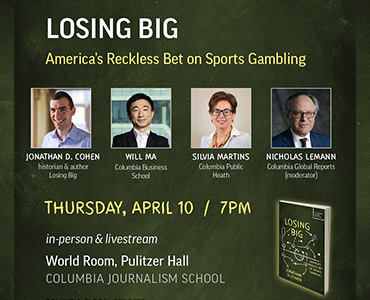

"It looks very much as if Western governments and armies have come into the region overthrowing governments, and then kind of washed their hands of it," Pelham said during a recent discussion with Safwan Masri, Columbia's Executive Vice President of Global Centers and Global Development, moderated by Columbia Global Reports director Nicholas Lemann. "When it came to trying to put something back in its place, the West was nowhere to be seen." It didn't only happen after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, but in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and elsewhere, right up to the Obama administration's overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. Perhaps the first thing that the next American President ought to do is think twice about any interventionism on the guise of democratic nation-building.

Rather than feeling hopeless, Pelham suggests that a solution should be found not by looking outward—say, to the West and liberal democracy—but by looking within the region's past pluralistic underpinnings. "Here’s an intriguing if partial answer," Black writes. "Consider the more tolerant ways of the Ottoman Empire, whose demise after the first world war gave way to today’s Arab nation states, a Jewish Israel and the growth of intolerance and sectarianism that is fomenting strife between Muslims and destroying ancient Christian communities."

Counterintuitively, less religion might not be the answer to the Middle East's sectarian problem. "The Ottomans, for example, managed an array of sects across their vast empire by delegating authority to sectarian patriarchs who resided in Istanbul, a practice known as the Millet System," Oathout writes. "Pelham asserts that the region’s religiosity isn’t going away, but peace will come more easily if Islam rediscovers its pluralist tendencies."

The West cannot be savior to the Middle East—the fate is in the region's hands. But there is cause for optimism. "Pluralism is not dead in the region," Pelham said. "But it does need a helping hand to revive, and where you can, offer that helping hand."