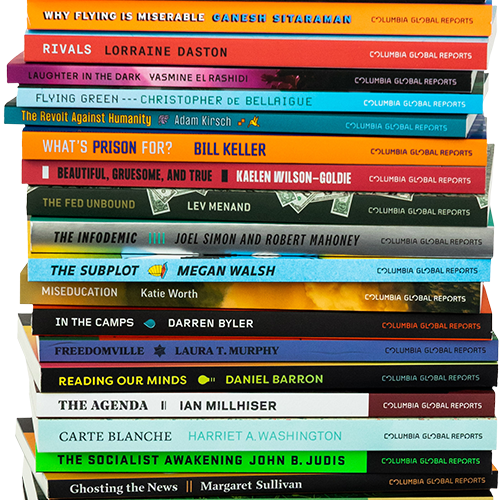

Ambitious Books.

Global Perspective.

Publishing concise nonfiction on the world’s most pressing issues

It’s CGR’s tenth anniversary! 🎉

Out in front on underreported issues for ten years and counting

Be the Most Interesting Person

in the Room

Subscribe to Columbia Global Reports

Find new ways of looking at the world with Columbia Global Reports. Our $85 subscription includes six paperbacks mailed in advance of publication directly to your doorstep.